Analemma image taken between 2021 and 2022, with images taken at 4 p.m. on a weekly basis, clouds permitting. The analemma was calibrated and overlaid with an image taken over Lake Varese in the late afternoon of the winter solstice in 2021, featuring one of the many swans that flock to the shores of Lake Varese in the foreground. Canon 400D + Sigma zoom lens 10 mm. Happy solstice!

Can you tell that today is a solstice by the tilt of the Earth? Yes. At a solstice, the Earth's terminator -- the dividing line between night and day -- is tilted the most. The featured time-lapse video demonstrates this by displaying an entire year on planet Earth in twelve seconds. From geosynchronous orbit, the Meteosat 9 satellite recorded infrared images of the Earth every day at the same local time. The video started at the September 2010 equinox with the terminator line being vertical: an equinox. As the Earth revolved around the Sun, the terminator was seen to tilt in a way that provides less daily sunlight to the northern hemisphere, causing winter in the north. At the most tilt, winter solstice occurred in the north, and summer solstice in the south. As the year progressed, the March 2011 equinox arrived halfway through the video, followed by the terminator tilting the other way, causing winter in the southern hemisphere -- and summer in the north. The captured year ends again with the September equinox, concluding another of the billions of trips the Earth has taken -- and will take -- around the Sun.

Eclipse tables in the Dresden Codex were based on lunar tables and adjusted for slippage over time. //

The Maya used three primary calendars: a count of days, known as the Long Count; a 260-day astrological calendar called the Tzolk’in; and a 365-day year called the Haab’. Previous scholars have speculated on how awe-inspiring solar or lunar eclipses must have seemed to the Maya, but our understanding of their astronomical knowledge is limited. Most Maya books were burned by Spanish conquistadors and Catholic priests. Only four hieroglyphic codices survive: the Dresden Codex, the Madrid Codex, the Paris Codex, and the Grolier Codex. //

They concluded that the codex’s eclipse tables evolved from a more general table of successive lunar months. The length of a 405-month lunar cycle (11,960 days) aligned much better with a 260-day calendar (46 x 260 =11,960) than with solar or lunar eclipse cycles. This suggests that the Maya daykeepers figured out that 405 new moons almost always came out equivalent to 46 260-day periods, knowledge the Maya used to accurately predict the dates of full and new moons over 405 successive lunar dates.

The daykeepers also realized that solar eclipses seemed to recur on or near the same day in their 260-day calendar and, over time, figured out how to predict days on which a solar eclipse might occur locally. “An eclipse happens only on a new moon,” said Lowry. “The fact that it has to be a new moon means that if you can accurately predict a new moon, you can accurately predict a one-in-seven chance of an eclipse. That’s why it makes sense that the Maya are revising lunar predicting models to have an accurate eclipse, because they don’t have to predict where the moon is relative to the ecliptic.” //

“The traditional interpretation was that you run through the table, eclipse by eclipse, and then you rebuilt the table every iteration,” said Lowry. “We figured out that if you do that, you’re going to miss the eclipses, and we know they didn’t. They made internal adjustments. We think they’d restart the table midway. When you do that, you go from having missed eclipses to having none. You would never miss an eclipse. So it’s not a calculated predictive table, it’s a calculated predictive table plus adjustments based on empirical observations over time.”

“This is the basis of true science, empirically collected, constant revision of expectations, built into a system of understanding planetary bodies, so that you can predict when something happens,” said Lowry.

On June 30, 1973, a supersonic jet screamed across the African sky at 58,000 feet, chasing darkness at 1,450 miles per hour. Inside Concorde 001, seven scientists peer through holes cut in the roof, watching the longest solar eclipse in human history unfold. //

Over Africa, the Moon’s shadow raced across Earth at over 1,300 miles per hour. Ground observers got seven minutes before the shadow moved on. But Concorde at Mach 2.2 could actually outrun the shadow, staying locked in totality for as long as fuel lasted. //

Height mattered as much as speed. At 58,000 feet, the aircraft flew above weather, water vapor, and atmospheric turbulence that would blur ground observations. The combination of speed, altitude, and precise navigation created a stable observatory hurtling through space faster than a rifle bullet.

Perseid Meteors from Durdle Door

The limestone arch in the foreground in Dorset, England is known as Durdle Door, a name thought to survive from a thousand years ago.

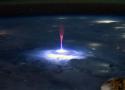

While most people witness only the familiar crack of thunder and flash of lightning from storms on Earth, brilliantly-colorful electric fireworks detonate much higher, in the thin air up to 55 miles overhead, easily seen from the ISS.

These brief spectacles – blue jets, red sprites, violet halos, ultraviolet rings – are collectively known as transient luminous events, or TLEs.

For decades, they eluded systematic study, appearing only in pilots’ anecdotes and the occasional lucky photograph.

The International Space Station (ISS) has changed that by offering an unobstructed seat above the storms, where specialized cameras and sensors capture every fleeting spark.

Sunrise, sunset, moon phase

Earth is expected to spin more quickly in the coming weeks, making some of our days unusually short. On July 9, July 22 and Aug. 5, the position of the moon is expected to affect Earth's rotation so that each day is between 1.3 and 1.51 milliseconds shorter than normal.

A powerful new observatory has unveiled its first images to the public, showing off what it can do as it gets ready to start its main mission: making a vivid time-lapse video of the night sky that will let astronomers study all the cosmic events that occur over ten years. //

Named after an astronomer famous for her research related to dark matter, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory is perched on a mountaintop in Chile. It's equipped with a specially-designed large telescope, as well as a car-sized digital camera that's the biggest such camera in the world.

The camera is controlled by an automated system that moves and points the telescope, snapping pictures again and again, to cover the entire sky every few days. Each image is so detailed, displaying it would take 400 ultra high-definition television screens.

By constantly comparing new images to ones taken before, the facility's computer systems will be able to spot anything in the sky that changes or moves or goes boom.

"It will be capable of really detecting things that actually change very rapidly," says Sandrine Thomas, deputy director of Rubin Observatory and the observatory's telescope and site project scientist. "That, in itself, will be unique to the world. No other telescope would be able to do that."

"It has such a wide field of view and such a rapid cadence that we do have that movie-like aspect to the night sky," she says.

The space agency’s astronomical models suggest that a lunar eclipse turned the moon red over Jerusalem on Friday, April 3, 33 AD — a date many scholars tie to Jesus’ death. //

The eclipse theory, originally floated by Oxford University researchers Colin Humphreys and W. Graeme Waddington, https://www.asa3.org/ASA/PSCF/1985/JASA3-85Humphreys.html

Neutron stars are incredibly dense objects about 10 miles (16 km) across. Only their immense gravity keeps the matter inside from exploding; if you brought a spoonful of neutron star to Earth, the lack of gravity would cause it to expand rapidly. //

A neutron star is the remnant of a massive star (bigger than 10 Suns) that has run out of fuel, collapsed, exploded, and collapsed some more. Its protons and electrons have fused together to create neutrons under the pressure of the collapse. The only thing keeping the neutrons from collapsing further is “neutron degeneracy pressure,” which prevents two neutrons from being in the same place at the same time.

Additionally, the star loses a lot of mass in the process and winds up only about 1.5 times the Sun’s mass. But all that matter has been compressed to an object about 10 miles (16 kilometers) across. A normal star of that mass would be more than 1 million miles (1.6 million km) across.

A tablespoon of the Sun, depending on where you scoop, would weigh about 5 pounds (2 kilograms) — the weight of an old laptop. A tablespoon of neutron star weighs more than 1 billion tons (900 billion kg) — the weight of Mount Everest. So while you could lift a spoonful of Sun, you can’t lift a spoonful of neutron star.

Black Hole

@konstructivizm

The James Webb telescope has discovered Jupiter-sized "planets" in space, free-floating and gravitationally unbound to any star

What has astonished scientists is that the planets are moving in pairs.

Astronomers are now trying to explain this phenomenon scientifically. They are inclined to believe that the objects were thrown out of their orbits due to gravitational disturbances.

NASA

6:10 AM · Apr 5, 2025

Rocket Diaries @rocket_diaries

·

6h

Webb just added a wild twist to our understanding of planetary formation—Jupiter-sized objects drifting through space in pairs, totally unbound to any star. Scientists think gravitational chaos may have ejected them, but why they’re paired up is still a mystery.

In For The Fun @InForTheFun_

·

13h

According to the International Astronomical Union, they are not planet. Because that's exactly how stupid their definition is. Defying something not based on its inherenet parameters like mass-radius (i.e. compactness), fusion etc, but on their orbital parameters. Go figure.

The Solar Eclipse Analemma Project

Image Credit & Copyright: Hunter Wells

Astronomers will find a lot more of these

City-killer asteroids the size of 2024 YR4 are fairly common in the inner Solar System. This asteroid was likely somewhere between 40 and 100 meters across, which is large enough to cause regional destruction on the planet, but small enough to be difficult to find with most telescopes. However, we should expect to find more of them in the coming years.

"An object the size of YR4 passes harmlessly through the Earth-Moon neighborhood as frequently as a few times per year," Richard Binzel, one of the world's leading asteroid experts and a professor of planetary sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told Ars. "The YR4 episode is just the beginning for astronomers gaining the capability to see these objects before they come calling through our neck of the woods.". //

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory, formerly known as the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, is nearing completion in Chile. Among its primary scientific objectives is finding small asteroids near Earth, and it is likely to find many. A little more than two years from now, the NEO Surveyor is scheduled to launch to a Sun-Earth Lagrange point. This NASA-backed instrument will survey the Solar System for threats to Earth. Finally, the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope due to launch in 2027 will not look directly for asteroids, but also is likely to find threats to Earth.

With all of these tools coming online, astronomers believe we are likely to find 10 or even 100 times more objects like 2024 YR4. //

In fact, the message people should take from this whole experience is that the Solar System is full of small rocks whizzing all around. And when it comes to asteroids and comets, knowledge is power.

Astronomers have detected over 5,800 confirmed exoplanets. One extreme class is ultra-hot Jupiters, of particular interest because they can provide a unique window into planetary atmospheric dynamics. According to a new paper published in the journal Nature, astronomers have mapped the 3D structure of the layered atmosphere of one such ultra-hot Jupiter-size exoplanet, revealing powerful winds that create intricate weather patterns across that atmosphere. A companion paper published in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics reported on the unexpected identification of titanium in the exoplanet's atmosphere as well.

The case of mistaken identity was quickly resolved, but scientists say it shows the need for transparency around spaceflight traffic in deep space.

On Jan. 2, the Minor Planet Center at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, announced the discovery of an unusual asteroid, designated 2018 CN41. First identified and submitted by a citizen scientist, the object’s orbit was notable: It came less than 150,000 miles (240,000 km) from Earth, closer than the orbit of the Moon. That qualified it as a near-Earth object (NEO) — one worth monitoring for its potential to someday slam into Earth.

But less than 17 hours later, the Minor Planet Center (MPC) issued an editorial notice: It was deleting 2018 CN41 from its records because, it turned out, the object was not an asteroid.

It was a car.

Lunar exploration is undergoing a renaissance. Dozens of missions, organized by multiple space agencies—and increasingly by commercial companies—are set to visit the Moon by the end of this decade. Most of these will involve small robotic spacecraft, but NASA’s ambitious Artemis program aims to return humans to the lunar surface by the middle of the decade.

There are various reasons for all this activity, including geopolitical posturing and the search for lunar resources, such as water-ice at the lunar poles, which can be extracted and turned into hydrogen and oxygen propellant for rockets. However, science is also sure to be a major beneficiary.

The Moon still has much to tell us about the origin and evolution of the Solar System. It also has scientific value as a platform for observational astronomy. //

Several types of astronomy would benefit. The most obvious is radio astronomy, which can be conducted from the side of the Moon that always faces away from Earth—the far side.

The lunar far side is permanently shielded from the radio signals generated by humans on Earth. During the lunar night, it is also protected from the Sun. These characteristics make it probably the most “radio-quiet” location in the whole solar system, as no other planet or moon has a side that permanently faces away from the Earth. It is, therefore, ideally suited for radio astronomy. //

At that time, most of the matter in the Universe, excluding the mysterious dark matter, was in the form of neutral hydrogen atoms. These emit and absorb radiation with a characteristic wavelength of 21 cm. Radio astronomers have been using this property to study hydrogen clouds in our own galaxy—the Milky Way—since the 1950s.

Because the Universe is constantly expanding, the 21 cm signal generated by hydrogen in the early Universe has been shifted to much longer wavelengths. As a result, hydrogen from the cosmic “dark ages” will appear to us with wavelengths greater than 10 m. The lunar far side may be the only place where we can study this. //

Moreover, there are craters at the lunar poles that receive no sunlight. Telescopes that observe the Universe at infrared wavelengths are very sensitive to heat and therefore have to operate at low temperatures. JWST, for example, needs a huge sun shield to protect it from the sun’s rays. On the Moon, a natural crater rim could provide this shielding for free. //

But there is also a tension here: human activities on the lunar far side may create unwanted radio interference, and plans to extract water-ice from shadowed craters might make it difficult for those same craters to be used for astronomy. As my colleagues and I recently argued, we will need to ensure that lunar locations that are uniquely valuable for astronomy are protected in this new age of lunar exploration.

astro_pettit

•

4d ago

Top 1% Poster

Comet C2024-G3 taken on GMT010/12:12. It is getting really bright as it moves towards perihelion. Most definitely eye visible. Being a handful of degrees from the sun, the zodiacal light is bright enough to interfere.

Nikon Z9, Nikon 50mm f1.2 lens, 1/5th second, f1.2, ISO 3200, adjusted Photoshop, denoise, levels, gamma, EV, color.

astro_pettit

•

2d ago

Top 1% Poster

Single photo with: Milkyway, Zodical light, Starlink satellites as streaks, stars as points, atmosphere on edge showing OH emission as burned umber (my favorite Crayon color), faint red upper f-region, soon to rise sun, and cities at night as streaks lit by the nearly full moon. Taken this morning from Dragon Crew 9 vehicle port window.

Nikon Z9, Sigma 14mm f1.4 lens, 15 seconds, f1.4, ISO 3200, adjusted Photoshop, levels, contrast, gamma, color, with homemade orbital sidereal drive to compensate for orbital pitch rate (4 degrees/sec). //

astro_pettit

OP

•

3h ago

Profile Badge for the Achievement Top 1% Poster Top 1% Poster

Black/white/colored specs are from cosmic ray damaged pixels. Unfortunately, there is a firmware bug in Z9 pixel map (Nikon is aware of and is fixing w next upgrade) that prevents it from working after a large number of damaged pixels occurs; pixel map worked for a few weeks on orbit and then quit with an error so now we can not use that feature. I am taking many dark frames and will fix my images after I return to Earth.

Almost no one ever writes about the Parker Solar Probe anymore.

Sure, the spacecraft got some attention when it launched. It is, after all, the fastest moving object that humans have ever built. At its maximum speed, goosed by the gravitational pull of the Sun, the probe reaches a velocity of 430,000 miles per hour, or more than one-sixth of 1 percent the speed of light. That kind of speed would get you from New York City to Tokyo in less than a minute. //

However, the smallish probe—it masses less than a metric ton, and its scientific payload is only about 110 pounds (50 kg)—is about to make its star turn. Quite literally. On Christmas Eve, the Parker Solar Probe will make its closest approach yet to the Sun. It will come within just 3.8 million miles (6.1 million km) of the solar surface, flying into the solar atmosphere for the first time.

Yeah, it's going to get pretty hot. Scientists estimate that the probe's heat shield will endure temperatures in excess of 2,500° Fahrenheit (1,371° C) on Christmas Eve, which is pretty much the polar opposite of the North Pole. //

I spoke with the chief of science at NASA, Nicky Fox, to understand why the probe is being tortured so. Before moving to NASA headquarters, Fox was the project scientist for the Parker Solar Probe, and she explained that scientists really want to understand the origins of the solar wind.

This is the stream of charged particles that emanate from the Sun's outermost layer, the corona. Scientists have been wondering about this particular mystery for longer than half a century, Fox explained.

"Quite simply, we want to find the birthplace of the solar wind," she said.

Way back in the 1950s, before we had satellites or spacecraft to measure the Sun's properties, Parker predicted the existence of this solar wind. The scientific community was pretty skeptical about this idea—many ridiculed Parker, in fact—until the Mariner 2 mission started measuring the solar wind in 1962.

As the scientific community began to embrace Parker's theory, they wanted to know more about the solar wind, which is such a fundamental constituent of the entire Solar System. Although the solar wind is invisible to the naked eye, when you see an aurora on Earth, that's the solar wind interacting with Earth's magnetosphere in a particularly violent way.

Only it is expensive to build a spacecraft that can get to the Sun. And really difficult, too.

Now, you might naively think that it's the easiest thing in the world to send a spacecraft to the Sun. After all, it's this big and massive object in the sky, and it's got a huge gravitational field. Things should want to go there because of this attraction, and you ought to be able to toss any old thing into the sky, and it will go toward the Sun. The problem is that you don't actually want your spacecraft to fly into the Sun or be going so fast that it passes the Sun and keeps moving. So you've got to have a pretty powerful rocket to get your spacecraft in just the right orbit. //

But you can't get around the fact that to observe the origin of the solar wind, you've got to get inside the corona. Fox explained that it's like trying to understand a forest by looking in from the outside. One actually needs to go into the forest and find a clearing. However, we can't really stay inside the forest very long—because it's on fire.

So, the Parker Solar Probe had to be robust enough to get near the Sun and then back into the coldness of space. Therein lies another challenge. The spacecraft is going from this incredibly hot environment into a cold one and then back again multiple times.

"If you think about just heating and cooling any kind of material, they either go brittle and crumble, or they may go like elastic with a continual change of property," Fox said. "Obviously, with a spacecraft like this, you can't have it making a major property change. You also need something that's lightweight, and you need something that's durable."

The science instruments had to be hardened as well. As the probe flies into the Sun there's an instrument known as a Faraday cup that hangs out to measure ion and electron fluxes from the solar wind. Unique technologies were needed. The cup itself is made from sheets of Titanium-Zirconium-Molybdenum, with a melting point of about 4,260° Fahrenheit (2,349° C). Another challenge came from the electronic wiring, as normal cables would melt. So, a team at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory grew sapphire crystal tubes in which to suspend the wiring, and made the wires from niobium.