Any gas can be converted into a liquid by simple compression, unless its temperature is below critical. Therefore, the division of substances into liquids and gases is largely conditional. The substances that we are used to considering as gases simply have very low critical temperatures and therefore cannot be in a liquid state at temperatures close to room temperature. On the contrary, the substances we classify as liquids have high critical temperatures (see table in §

).

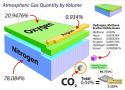

All gases that make up the air (except carbon dioxide) have low critical temperatures. Their liquefaction therefore requires deep cooling.

There are many types of machines for producing liquid gases, in particular liquid air.

In modern industrial plants, significant cooling and liquefaction of gases is achieved by expansion under thermal insulation conditions.

blackhawk887 Ars Tribunus Angusticlavius

9y

19,694

100% TNT equivalent is crazy. Even 25% is probably twice a reasonable figure. The FAA uses 14% for LOX/hydrogen and 10% for LOX/kerosene. Hydrogen is more than twice as energetic per mass of methane, and kerosene about 80% as energetic as methane.

LOX and liquid methane are miscible, unlike the other combinations, but there aren't any plausible scenarios where you'd get better mixing than a rocket falling back on the pad shortly after liftoff, which both kerolox and hydrolox are also perfectly capable of doing. //

mattlindn Ars Centurion

7y

231

NASA's current blast range evacuation area ranges from 3 to 4 miles as shown in the diagrams in this article (I measured it on google maps).

It's worth mentioning that the privately run Rocket Ranch down in South Texas where people can pay money to get closer to the Starship launches is only 3.9 miles from the launch site. The people who watch from the Mexico can get as close as 2.4 miles.

Where most people (including myself) watch(ed) from, South Padre Island, is almost exactly 5 miles away.

So yeah this seems kind of excessive. //

Jack56 Ars Scholae Palatinae

7y

672

For the nth time, a fuel-oxidiser explosion is not a detonation. It is a deflagration. They are far less violent. An intimate mixture of gaseous oxygen and methane can detonate but liquid methane and liquid oxygen cannot mix intimately - are not miscible - because methane is a solid at lox temperatures, especially the sub-cooled lox which Starship uses. A detonation takes place in under a millisecond. Deflagrations are fires. I’m not saying it wouldn’t be bad but comparisons with an energetically equivalent mass of TNT are way out of line. //

mattlindn Ars Centurion

7y

231

Jack56 said:

For the nth time, a fuel-oxidiser explosion is not a detonation. It is a deflagration. They are far less violent. An intimate mixture of gaseous oxygen and methane can detonate ....

Didn't think about this, but yes you're correct. The boiling point of Oxygen is 90.2 K and the melting point of Methane is 90.7 K. If you mix the two together, before any Methane can melt all the oxygen has to boil off. Though there should still be some local melting given the outside air temperatures are MUCH warmer than the liquid oxygen.

Though at the same time given the temperatures are so close together I don't think much Methane will freeze before an explosion happens. So maybe the point is moot? //

SpikeTheHobbitMage Ars Scholae Palatinae

3y

1,745

Person_Man said:

I have to imagine a fully fueled stack with optimal mixing for the biggest explosion would probably be the largest non nuclear explosion ever.

Most of Starship's propellant is oxygen. The full stack only carries 1030t of methane (330t on Ship, 700t on SuperHeavy). Methane also has a TNT equivalent of only 0.16. Using the omnicaluclator, I get 1030t of methane* = 164.8t of TNT. That doesn't even make the top 10 list.

*omnicalculator lists natural gas, which is mostly methane. //

blackhawk887 Ars Tribunus Angusticlavius

9y

19,694

mattlindn said:

Didn't think about this, but yes you're correct. The boiling point of Oxygen is 90.2 K and the melting point of Methane is 90.7 K. If you mix the two together, ...

Mixing with oxygen should depress the freezing point of methane. For example, if you take water at its freezing point, and mix it equally with alcohol that is itself, say, 10 degrees colder than the freezing point of water, the resulting mix will be well below 0 C but will not contain any frozen water.

Also, you can mix butane and water under a little pressure, even though at atmospheric pressure butane boils a half-degree below the freezing point of water. They aren't miscible, but that's just because of polarity - they are happy to both be liquids at the same temperature and a little pressure.

Methane and LOX are considered miscible and were even considered for monopropellants at various mix ratios. The mixture is reportedly a bit shock sensitive though. //

SpikeTheHobbitMage Ars Scholae Palatinae

3y

1,745

Mad Klingon said:

For the many debating using eminent domain to expand launch facilities, that would likely be the simple part of the issue. Most of that area is considered sensitive wildlife area and dealing with the current piles environmental regulations and paperwork could take decades for a major expansion. Look at all the grief SpaceX gets when they build on the relatively bland bit of Texas coast they are currently using. It would be much worse at the Florida site.One of the great legacies of Apollo was we got a well built out area for launching stuff before most of the environmental legislation was passed.

One of the great legacies of Apollo was that the exclusion zone around Cape Canaveral preserved enough of the wetlands in good enough condition to become a protected nature reserve.

The late, great Dr. Petr Beckmann was editor of the great journal Access to Energy, founder of the dissident physics journal Galilean Electrodynamics (brochures and further Beckmann info here; further dissident physics links), author of The Health Hazards of NOT Going Nuclear (Amazon; PDF version) and the pamphlets The Non-Problem of Nuclear Waste and Why “Soft” Technology Will Not Be America’s Energy Salvation. (See also my post Access to Energy (archived comments), and this post.)

I just came across another favorite piece of his and have scanned it in: Economics as if Some People Mattered (review of Small is Beautiful by E.F. Schumacher), first published in Reason (October 1978), and reprinted in Free Minds & Free Markets: Twenty-Five Years of Reason (1993). Those (including some libertarians and fellow travelers) who also have a thing for “smallness” and bucolic pastoralism should give this a read.

Small is Beautiful is the title of a book by E.F. Schumacher. It is also a slogan describing a state of mind in which people clamor for the rural idyll that (they think) comes with primitive energy sources, small-scale production, and small communities. Yet much–perhaps most–of their clamor is not really for what they consider small and beautiful; it is for the destruction of what they consider big and ugly.

… The free market does not, of course, eradicate human greed, but it directs it into channels that the consumer the maximum benefit, for it is he who benefits from the competition of”profit-greedy” businessmen. The idea that the free market is highly popular among businessmen is one that is widespread, but not among sound economists. It was not very popular in 1776, when Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations was published, and it has not become terribly popular with all of them since–which is not surprising, for the free market benefits the consumer but disciplines the businessman.

If the free market is so popular with business, what are all those business lobbies doing in Washington? The shipping lobby wants favors for U.S. ships; the airlines yell rape and robbery when deregulation from the governmental CAB cartel threatens; the farmers’ lobby clamors for more subsidies. What all these lobbies are after is not a freer market but a bigger nipple on the federal sow.

It's a plot device beloved by science fiction: our entire universe might be a simulation running on some advanced civilization's supercomputer. But new research from UBC Okanagan has mathematically proven this isn't just unlikely—it's impossible.

Dr. Mir Faizal, Adjunct Professor with UBC Okanagan's Irving K. Barber Faculty of Science, and his international colleagues, Drs. Lawrence M. Krauss, Arshid Shabir and Francesco Marino have shown that the fundamental nature of reality operates in a way that no computer could ever simulate.

Their findings, published in the Journal of Holography Applications in Physics, go beyond simply suggesting that we're not living in a simulated world like The Matrix. They prove something far more profound: the universe is built on a type of understanding that exists beyond the reach of any algorithm. //

"Drawing on mathematical theorems related to incompleteness and indefinability, we demonstrate that a fully consistent and complete description of reality cannot be achieved through computation alone," Dr. Faizal explains. "It requires non-algorithmic understanding, which by definition is beyond algorithmic computation and therefore cannot be simulated. Hence, this universe cannot be a simulation."

Co-author Dr. Lawrence M. Krauss says this research has profound implications. "The fundamental laws of physics cannot be contained within space and time, because they generate them. It has long been hoped, however, that a truly fundamental theory of everything could eventually describe all physical phenomena through computations grounded in these laws. Yet we have demonstrated that this is not possible. A complete and consistent description of reality requires something deeper—a form of understanding known as non-algorithmic understanding." //

More information: Mir Faizal et al, Consequences of Undecidability in Physics on the Theory of Everything, Journal of Holography Applications in Physics (2025). DOI: 10.22128/jhap.2025.1024.1118. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2507.22950 https://dx.doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2507.22950

"If you bring a charged particle like an electron near the surface, because the helium is dielectric, it'll create a small image charge underneath in the liquid," said Pollanen. "A little positive charge, much weaker than the electron charge, but there'll be a little positive image there. And then the electron will naturally be bound to its own image. It'll just see that positive charge and kind of want to move toward it, but it can't get to it, because the helium is completely chemically inert, there are no free spaces for electrons to go."

Obviously, to get the helium liquid in the first place requires extremely low temperatures. But it can actually remain liquid up to temperatures of 4 Kelvin, which doesn't require the extreme refrigeration technologies needed for things like transmons. Those temperatures also provide a natural vacuum, since pretty much anything else will also condense out onto the walls of the container. //

Erbium68 Wise, Aged Ars Veteran

8m

1,829

Subscriptor

The trap and what they have achieved so far is very interesting. I have to say the mere 40dB of the amplifier (assuming that is voltage gain not power gain) is remarkable for what is surely a very tiny signal (and that is microwatts out, not megawatts).

But, as a practical quantum computer?

It still has to run at below 4K and there still has to be a transition to electronics at close to STP. The refrigeration is going to be bulky and power consuming. Of course the answer to that is to run a lot of qubits in one envelope, but getting there is going to take a long time.

We seem to have had the easy technological hits. The steam engine, turbines, IC engines, dynamos and alternators all came with relatively simple fabrication techniques and run at room temperature except for the hot bits. Early electronics began with a technical barrier - vacuum enclosures - but never needed to scale these beyond single or dual devices, and by the time that became a barrier to progress, transistors were already happening and it was then a matter of scaling size down and gates up. The electronics revolution happened at room temperature, maybe with some air cooling or liquid cooling for high powers.

Now we have the issue that getting a few gates to work needs a vacuum chamber at below 4K. Scaling is going to be expensive. And progress in conventional semiconductors will continue.

This approach may be wildly successful like epitaxial silicon technology. But it may also flop like the Wankel engine - the existing technology advancing faster than the initially complex and new technology can. //

dmsilev Ars Tribunus Angusticlavius

16y

6,561

Subscriptor

Erbium68 said:

The trap and what they have achieved so far is very interesting. I have to say the mere 40dB of the amplifier (assuming that is voltage gain not power gain) is remarkable for what is surely a very tiny signal (and that is microwatts out, not megawatts).

But, as a practical quantum computer?

It still has to run at below 4K and there still has to be a transition to electronics at close to STP. The refrigeration is going to be bulky and power consuming. Of course the answer to that is to run a lot of qubits in one envelope, but getting there is going to take a long time.

Compared to a datacenter computing system, it's actually not all that hugely power consuming. In rough numbers, 10-12 kW of electricity will get you a pulse tube cryocooler which can cool 50 or 100 kilograms of stuff down to about 4 K and keep it at that temperature with 1-2 W of heat load at the cold end. That's enough for a lot of 4 K qubits and first-stage electronics. Add in an extra kW for another pump and you can cool maybe 10 kg to ~1.5 K, with about 0.5 W of headroom. A couple more pumps at a kW or so each, some helium3 and a lot of expensive plumbing, and you have a dilution refrigerator, 20 mK with about 20-40 uW of headroom.

Compare that 10-15 kW with the draw from a single rack of AI inference engines.

Inside a laboratory nestled above the mist of the forests of South Dakota, scientists are searching for the answer to one of science's biggest questions: why does our Universe exist?

They are in a race for the answer with a separate team of Japanese scientists – who are several years ahead.

The current theory of how the Universe came into being can't explain the existence of the planets, stars and galaxies we see around us. Both teams are building detectors that study a sub-atomic particle called a neutrino in the hope of finding answers.

The US-led international collaboration is hoping the answer lies deep underground, in the aptly named Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (Dune). //

When the Universe was created two kinds of particles were created: matter – from which stars, planets and everything around us are made – and, in equal amounts, antimatter, matter's exact opposite.

Theoretically the two should have cancelled each other out, leaving nothing but a big burst of energy. And yet, here we – as matter – are. //

Scientists believe that the answer to understanding why matter won – and we exist – lies in studying a particle called the neutrino and its antimatter opposite, the anti-neutrino.

They will be firing beams of both kinds of particles from deep underground in Illinois to the detectors at South Dakota, 800 miles away.

This is because as they travel, neutrinos and anti-neutrinos change ever so slightly.

The scientists want to find out whether those changes are different for the neutrinos and anti-neutrinos. If they are, it could lead them to the answer of why matter and anti-matter don't cancel each other out. //

Half a world away, Japanese scientists are using shining golden globes to search for the same answers. Gleaming in all its splendour it is like a temple to science, mirroring the cathedral in South Dakota 6,000 miles (9,650 km) away. The scientists are building Hyper-K - which will be a bigger and better version of their existing neutrino detector, Super-K.

The Japanese-led team will be ready to turn on their neutrino beam in less than three years, several years earlier than the American project. Just like Dune, Hyper-K is an international collaboration. Dr Mark Scott of Imperial College, London believes his team is in pole position to make one of the biggest ever discoveries about the origin of the Universe.

"We switch on earlier and we have a larger detector, so we should have more sensitivity sooner than Dune," he says.

Having both experiments running together means that scientists will learn more than they would with just one, but, he says, "I would like to get there first!"

There's a lot of matter around, which ensures that any antimatter produced experiences a very short lifespan. Studying antimatter, therefore, has been extremely difficult. But that's changed a bit in recent years, as CERN has set up a facility that produces and traps antimatter, allowing for extensive studies of its properties, including entire anti-atoms.

Unfortunately, the hardware used to capture antiprotons also produces interference that limits the precision with which measurements can be made. So CERN decided that it might be good to determine how to move the antimatter away from where it's produced. Since it was tackling that problem anyway, CERN decided to make a shipping container for antimatter, allowing it to be put on a truck and potentially taken to labs throughout Europe. //

The problem facing CERN comes from its own hardware. The antimatter it captures is produced by smashing a particle beam into a stationary target. As a result, all the anti-particles that come out of the debris carry a lot of energy. If you want to hold on to any of them, you have to slow them down, which is done using electromagnetic fields that can act on the charged antimatter particles. Unfortunately, as the team behind the new work notes, many of the measurements we'd like to do with the antimatter are "extremely sensitive to external magnetic field noise."

In short, the hardware that slows the antimatter down limits the precision of the measurements you can take.

The obvious solution is to move the antimatter away from where it's produced. But that gets tricky very fast. The antimatter containment device has to be maintained as an extreme vacuum and needs superconducting materials to produce the electromagnetic fields that keep the antimatter from bumping into the walls of the container. All of that means a significant power supply, along with a cache of liquid helium to keep the superconductors working. A standard shipping container just won't do. //

So the team at CERN built a two-meter-long portable containment device. On one end is a junction that allows it to be plugged into the beam of particles produced by the existing facility. That junction leads to the containment area, which is blanketed by a superconducting magnet. Elsewhere on the device are batteries to ensure an uninterrupted power supply, along with the electronics to run it all. The whole setup is encased in a metal frame that includes lifting points that can be used to attach it to a crane for moving around. //

There's a facility being built in Düsseldorf, Germany, for antiproton experiments, nearly 800 kilometers and eight hours away by road. If the delivery can be made successfully—and it appears we are just a liquid helium supply away from getting it to work—the new facility in Germany should allow measurements with a precision of over 100 times better than anything that has been achieved at CERN.

Researchers at CERN have created and trapped antihydrogen in an attempt to study the underpinnings of the standard model of physics. Antihydrogen is made of antiparticles, specifically an antiproton and a positron, instead of the proton and an electron that are present in natural hydrogen. It has the same mass but opposite charge of its normal matter counterparts.

Antimatter has a bad reputation for being dangerous because it annihilates on contact with regular matter, releasing prodigious amounts of energy. However, the clever Ars reader will note that they have not been annihilated by the antimatter produced at CERN. The reality is that if you gathered all of the antimatter CERN has ever created, you wouldn't garner enough energy to power your laptop through reading this article. //

Antiparticles behave predictably in the presence of electric or magnetic fields and so can be contained in a special magnetic container called a Penning trap. Antihydrogen, which has no net electric charge, is much harder to contain. //

The ALPHA trap can confine antihydrogen in the ground state if it's kept at temperatures of less than half a Kelvin.

One challenge of this experiment is mixing the antiprotons and positrons at relatively low velocities such that antihydrogen can form efficiently. The efficiency is relative; The authors had to mix 10 million positrons with 700 million antiprotons in order to get get 38 certifiable antihydrogen events. //

It remains one of the largest unsolved problems in physics today as to why the Universe contains more regular matter than antimatter. Symmetry would suggest the Universe should have produced equal parts matter and antimatter, which would have annihilated—because we are here, we know this was not the case. Now that they have a bit of antihydrogen on hand, the researchers will test fundamental symmetries in nature (charge conjugation/parity/time reversal) by examining the excited states of antihydrogen. //

Boskone Ars Legatus Legionis

24y

12,399

Subscriptor

UltimateLemon":316tohp9 said:

When can we start weaponizing it?

As soon as we have significant amounts, and apparently figure out how to stabilize it enough to mix with matter.

1kg antimatter mixing with 1kg matter yields something like 50 megatons. (Which means that a 3oz bottle of antiperspirant is about 4 megatons. Now TSA's really going to have an aneurysm. </rimshot>) //

Bicentennial Douche Ars Legatus Legionis

21y

10,339

Subscriptor

matt_w_1":1ow1041j said:

how do you exam anti-matter? I assume throwing regular light at it would destroy it?

Duh, by using anti-light of course! The problem with that is that its too dark to see what you are doing. //

Hat Monster Ars Legatus Legionis

24y

47,680

Subscriptor

Now then, all we need is antioxygen to mix with our antihydrogen and we can make antiwater which will start fires instead of extinguishing them! //

mr wonka Ars Praetorian

17y

414

bedward":2u0orn9j said:

Boskone":2u0orn9j said:

1kg antimatter mixing with 1kg matter yields something like 50 megatons. (Which means that a 3oz bottle of antiperspirant is about 4 megatons. Now TSA's really going to have an aneurysm. </rimshot>)It's not that big a deal; sniffer dogs would pick out the matching 3oz bottle of perspirant pretty easily.

Bedward needs to buy me a new keyboard.

Why do shockwaves extend past the body that created them? As seen in this photo, the shock doesn’t stop in the air the plane is effecting, but continues on. I always assumed it was high pressure air from the shock extending out, but now I’m not too sure. //

Shocks are not because of the pressure. Shocks happen because of the turning -- the pressure jump is a result of the shock. – Rob McDonald Mar 14, 2024 at 17:27

A shock wave generated at 30,000 feet at Mach 1 cannot be heard on the ground for precisely the reason you surmise in your comment.

The US Air Force has conducted tests with supersonic aircraft and has this to say:

Under standard atmospheric conditions, air temperature decreases with increased altitude. For example, when sea-level temperature is 58 degrees Fahrenheit, the temperature at 30,000 feet drops to minus 49 degrees Fahrenheit. This temperature gradient helps bend the sound waves upward. Therefore, for a boom to reach the ground, the aircraft speed relative to the ground must be greater than the speed of sound at the ground. For example, the speed of sound at 30,000 feet is about 670 miles per hour, but an aircraft must travel at least 750 miles per hour (Mach 1.12, where Mach 1 equals the speed of sound) for a boom to be heard on the ground.

We have proposed that other planetary forces and phenomena, such as albedo, play a much larger role than CO2 in global warming or temperature variations.

The basic laws of physics and thermodynamics are not in support of efficient processing of CO2 using DAC. This is because dilute molecules of CO2 in air prefer to randomly mix and achieve maximum disorder or entropy per The Second Law of Thermodynamics.

Per Sherwood, trace amounts of CO2 molecules in an air mixture are difficult and costly to separate.

Capturing CO2 by DAC takes at least as much energy as that is contained in the fossil fuels that produced the carbon dioxide in the first place, per Keynumbers. //

Extra Thoughts: What Might Happen if CO₂ is Removed from the Air ?

-

If CO₂ is removed from the air in some significant quantity, CO₂ may outgas from the other sinks (land, oceans, lakes) to replace the removed CO₂. The reverse is true as well: when CO₂ is increased in the air, land/oceans/lakes) will uptake more CO₂ until a new quasi-equilibrium state is possibly reached over time.

-

A recent Nature Climate Change paper discusses the possible effect of CO₂ removal on the global carbon cycle. The paper notes that removing tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere might not be effective, because the shifting atmospheric chemistry could, in turn, affect how readily land and oceans release their CO₂, aka Le Chatelier’s principle. Another reference discusses the same concepts, and it is noted that both rely on synthetic models, like most climate change theory.

-

Handwaving synthetic climate models: a general rule that has been propagated is that for every tonne that ends up being emitted from fossil fuels or “land use changes”, a quarter gets absorbed by trees, another quarter by the ocean and the remaining half gets left in the atmosphere. I have not seen any hard data that backs this up. It basically says half the CO₂ emitted by man is left over and can’t be absorbed or re-equilibrated.

For context, the most powerful particle accelerator on Earth, the Large Hadron Collider, accelerates protons to an energy of 7 Tera-electronVolts (TeV). The neutrino that was detected had an energy of at least 60 Peta-electronVolts, possibly hitting 230 PeV. That also blew away the previous records, which were in the neighborhood of 10 PeV.

Attempts to trace back the neutrino to a source make it clear that it originated outside our galaxy, although there are a number of candidate sources in the more distant Universe. //

Neutrinos, to the extent they're famous, are famous for not wanting to interact with anything. They interact with regular matter so rarely that it's estimated you'd need about a light-year of lead to completely block a bright source of them. Every one of us has tens of trillions of neutrinos passing through us every second, but fewer than five of them actually interact with the matter in our bodies in our entire lifetimes.

The only reason we're able to detect them is that they're produced in prodigious amounts by nuclear reactions, like the fusion happening in the Sun or a nuclear power plant. We also stack the deck by making sure our detectors have a lot of matter available for the neutrinos to interact with.

What if the particles we hunt for in high-energy physics laboratories—those fleeting fragments of matter and energy—aren’t just out there, waiting to be found, but are, in some way, created by the very act of looking? The anomalon particle, first observed as an inexplicable anomaly in nuclear physics experiments, might not just be a curiosity of nature but a profound clue to a deeper truth: that consciousness itself could shape the physical world. This provocative idea finds its most compelling champion in the late Robert G. Jahn, a visionary physicist who spent decades exploring the mysterious interplay between mind and matter.

Here's the math behind making a star-encompassing megastructure.

In 1960, visionary physicist Freeman Dyson proposed that an advanced alien civilization would someday quit fooling around with kindergarten-level stuff like wind turbines and nuclear reactors and finally go big, completely enclosing their home star to capture as much solar energy as they possibly could. They would then go on to use that enormous amount of energy to mine bitcoin, make funny videos on social media, delve into the deepest mysteries of the Universe, and enjoy the bounties of their energy-rich civilization.

But what if the alien civilization was… us? What if we decided to build a Dyson sphere around our sun? Could we do it? How much energy would it cost us to rearrange our solar system, and how long would it take to get our investment back? Before we put too much thought into whether humanity is capable of this amazing feat, even theoretically, we should decide if it’s worth the effort. Can we actually achieve a net gain in energy by building a Dyson sphere? //

Even if we were to coat the entire surface of the Earth in solar panels, we would still only capture less than a tenth of a billionth of all the energy our sun produces. Most of it just radiates uselessly into empty space. We’ll need to keep that energy from radiating away if we want to achieve Great Galactic Civilization status, so we need to do some slight remodeling. We don’t want just the surface of the Earth to capture solar energy; we want to spread the Earth out to capture more energy. //

For slimmer, meter-thick panels operating at 90 percent efficiency, the game totally changes. At 0.1 AU, the Earth would smear out a third of the sun, and we would get a return on our energy investment in around a year. As for Jupiter, we wouldn’t even have to go to 0.1 AU. At a distance about 30 percent further out than that, we could achieve the unimaginable: completely enclosing our sun. We would recoup our energy cost in only a few hundred years, and we could then possess the entirety of the sun’s output from then on. //

MichalH Smack-Fu Master, in training

4y

62

euknemarchon said:

I don't get it. Why wouldn't you use asteroid material?

The mass of all asteroids amounts to only 3% of the earth's moon. Not worth chasing them down, I'd guess. //

DCStone Ars Tribunus Militum

14y

2,313

"But [Jupiter]’s mostly gas; it only has about five Earth’s worth of rocky material (theoretically—we’re not sure) buried under thousands of kilometers of mostly useless gas. We'd have to unbind the whole dang thing, and then we don’t even get to use most of the mass of the planet."

Hmm. If we can imagine being able to unbind rocky planets, we can also imagine fusing the gas atmosphere of Jupiter to make usable material (think giant colliders). Jupiter has a mass of about 1.9 x 10^27 kg, of which ~5% is rocky core. We'd need to make some assumptions about the energy required to fuse the atmosphere into something usable (silicon and oxygen to make silicates?) and the efficiency of that process. Does it do enough to change the overall calculation though? //

Dark Jaguar Ars Tribunus Angusticlavius

9y

11,066

The bigger issue is the sphere wouldn't be gravitationally locked in place because the sun is cancelling it's own pull in every direction. Heck even Ringworld had to deal with this flaw in the sequel. That's why these days the futurists talking about enclosing the sun recommend "Dyson swarming" instead.

Edit: A little additional note. You can't really get the centrifugal force needed to generate artificial gravity across an entire sphere like you can with a ring. A swarm doesn't negate this. If you orbit fast enough to generate that artificial gravity, you're now leaving the sun behind. Enjoy drifting endlessly! No, rather each of these swarm objects are just going to have to rotate themselves decently fast.

Four golden lessons -- advice to students at the start of their scientific careers.

-- Steven Weinberg

Nature, Vol 426, 27 Nov 2003

The Hafele–Keating experiment was a test of the theory of relativity. In 1971,[1] Joseph C. Hafele, a physicist, and Richard E. Keating, an astronomer, took four caesium-beam atomic clocks aboard commercial airliners. They flew twice around the world, first eastward, then westward, and compared the clocks in motion to stationary clocks at the United States Naval Observatory. When reunited, the three sets of clocks were found to disagree with one another, and their differences were consistent with the predictions of special and general relativity. //

Hafele, an assistant professor of physics at Washington University in St. Louis, was preparing notes for a physics lecture when he did a back-of-the-envelope calculation showing that an atomic clock aboard a commercial airliner should have sufficient precision to detect the predicted relativistic effects.[11] He spent a year in fruitless attempts to get funding for such an experiment, until he was approached after a talk on the topic by Keating, an astronomer at the United States Naval Observatory who worked with atomic clocks.[11]

Hafele and Keating obtained $8000 in funding from the Office of Naval Research[12] for one of the most inexpensive tests ever conducted of general relativity. Of this amount, $7600 was spent on the eight round-the-world plane tickets,[13] including two seats on each flight for "Mr. Clock." They flew eastward around the world, ran the clocks side by side for a week, and then flew westward. The crew of each flight helped by supplying the navigational data needed for the comparison with theory. In addition to the scientific papers published in Science,[5][6] there were several accounts published in the popular press and other publications. //

Presently both gravitational and velocity effects are routinely incorporated, for example, into the calculations used for the Global Positioning System.

Do split flaps produce lift? I don't see how, because there is no change in camber. It seems like an upside down speed break, producing only drag.

A:

Well, after all lift is created by deflecting air downward, which is exactly what a split flap does - although in a very inefficient way i.e. with a lot of drag.

This NACA TN shows how Cl and Cd increase with the deflection δf of the split flap (left plot):

They hold the keys to new physics. If only we could understand them.

Somehow, neutrinos went from just another random particle to becoming tiny monsters that require multi-billion-dollar facilities to understand. And there’s just enough mystery surrounding them that we feel compelled to build those facilities since neutrinos might just tear apart the entire particle physics community at the seams.

It started out innocently enough. Nobody asked for or predicted the existence of neutrinos, but there they were in our early particle experiments. Occasionally, heavy atomic nuclei spontaneously—and for no good reason—transform themselves, with either a neutron converting into a proton or vice-versa. As a result of this process, known as beta decay, the nucleus also emits an electron or its antimatter partner, the positron.

There was just one small problem: Nothing added up. The electrons never came out of the nucleus with the same energy; it was a little different every time. Some physicists argued that our conceptions of the conservation of energy only held on average, but that didn’t feel so good to say out loud, so others argued that perhaps there was another, hidden particle participating in the transformations. Something, they argued, had to sap energy away from the electron in a random way to explain this.

Eventually, that little particle got a name, the neutrino, an Italian-ish word meaning “little neutral one.” //

All this is… fine. Aside from the burning mystery of the existence of particle generations in the first place, it would be a bit greedy for one neutrino to participate in all possible reactions. So it has to share the job with two other generations. It seemed odd, but it all worked.

And then we discovered that neutrinos had mass, and the whole thing blew up. //

Nazgutek Ars Scholae Palatinae

23y

866

That was a fun read. I feel like I've climbed a single Dunning-Kruger step and now I feel like I know that I know less about the universe than I did before reading this article! //

NameRedacted Ars Praetorian

7y

445

Subscriptor

karadoc said:

such that relative to you the neutrino's direction of motion would then be reversed (compared to before you overtook it)... so then I'd expect that to be a right-handed neutrino from the point of view of that speedy observer.

I may be very wrong here, but I think that the entire point of chirality is that you can’t just reverse it by changing your perspective.NameRedacted Ars Praetorian

7y

445

Subscriptor

karadoc said:

such that relative to you the neutrino's direction of motion would then be reversed (compared to before you overtook it)... so then I'd expect that to be a right-handed neutrino from the point of view of that speedy observer.

I may be very wrong here, but I think that the entire point of chirality is that you can’t just reverse it by changing your perspective. //

NameRedacted Ars Praetorian

7y

445

Subscriptor

Back when I first graduated with my engineering degree, I really wanted to go back and get a PHD in physics because I loved QM so much.

Every time I read one of these articles, I’m glad I didn’t. Don’t get me wrong, this stuff is exciting: but I don’t think I could handle how much the universe “wants” to perplex us.

I have little doubt that the physics world will need to completely change everything to figure out all four of the big “mysteries”: Neutrinos, Dark Matter, Dark Energy, and the Hubble Constant. I also have little doubt that the solution will be complex, expensive, and be an advancement on the level of QM (I.e. atomic energy and semiconductors).

I hope I’m alive for when it happens, but *$&@ am I ever glad I haven’t spent my career trying to sort it out. //

Simk Smack-Fu Master, in training

4y

56

Subscriptor++

I really enjoyed that article! I'm none the wiser for having read it, but that seems fitting for the subject matter. //

neil_w Ars Praetorian

13y

464

Well, the properties of neutrinos don’t line up like this. They’re weird. When we see an electron-neutrino in an experiment, we’re not seeing a single particle with a single set of properties. Instead we’re seeing a composite particle—a trio of particles that exist in a quantum superposition with each other that all work together to give the appearance of an electron-neutrino.

For a moment I considered just closing the browser tab after reading this paragraph.

This was a very good article, trying to explain the nearly unexplainable. Hat tip to the physicists who are able to grasp it all. //

dmsilev Ars Praefectus

14y

5,375

Subscriptor

The sum of all three neutrino masses cannot be more than around 0.1 eV/c2

The absolute value of the square of the difference between m2 and m1 is 0.000074 eV/c2

The absolute value of the square of the difference between m2 and m3 is 0.00251 eV/c2

One thing which the article didn't mention is that there's an additional question hiding in these constraints. Usually, mass scales with family; the electron is lighter than the muon is lighter than the tau, and similarly for the quarks. We assume that that's the case for neutrinos as well, that m1 (the major constituent of electron neutrinos) is less than m2 is less than m3. That's called the "normal hierarchy" solution. However, the data doesn't prove that. There's also an "inverted hierarchy" fully consistent with the data which swaps the ordering. And we can't tell which one is correct. The only reason for the somewhat prejudicial names "normal" and "inverted" is the sense of elegance that the laws of physics should be somewhat consistent.

Dear Dr. Zoomie – I was watching The Man in the High Castle and there was a bit about weapons-grade uranium posing a health risk to people around it. Is this true? //

The short version is that uranium – even highly enriched uranium – is simply not very radioactive. I can confirm this from personal measurements – I’ve made radiation dose rate measurements on depleted uranium, natural uranium, and enriched uranium and none of them are very radioactive. Here’s why: //

. It takes about 100 rem to cause radiation sickness, about 400 rem to give someone a 50% chance of death (without medical treatment), and nearly 1000 rem to be fatal. With a dose rate of 1 R/hr at a distance of 1 meter this part’s easy – it’ll take 25 hours of exposure to cause a change in blood cell counts, 400 hours to give a 50% risk of death, and 1000 hours to cause death. At a speed of 60 mph it takes about 50 hours to cross the US – not even enough time to develop radiation sickness. And that’s for a person sitting for that whole time at a distance of 1 meter from the uranium...

What price common sense? • June 11, 2024 7:30 AM

@Levi B.

“Those who are not familiar with the term “bit-squatting” should look that up”

Are you sure you want to go down that rabbit hole?

It’s an instant of a general class of problems that are never going to go away.

And why in

“Web servers would usually have error-correcting (ECC) memory, in which case they’re unlikely to create such links themselves.”

The key word is “unlikely” or more formally “low probability”.

Because it’s down to the fundamentals of the universe and the failings of logic and reason as we formally use them. Which in turn has been why since at least as early as the ancient Greeks through to 20th Century, some of those thinking about it in it’s various guises have gone mad and some committed suicide.

To understand why you need to understand why things like “Error Correcting Codes”(ECC) will never by 100% effective and deterministic encryption systems especially stream ciphers will always be vulnerable. //

No matter what you do all error checking systems have both false positive and false negative results. All you can do is tailor the system to that of the more probable errors.

But there are other underlying issues, bit flips happen in memory by deterministic processes that apparently happen by chance. Back in the early 1970’s when putting computers into space became a reality it was known that computers were effected by radiation. Initially it was assumed it had to be of sufficient energy to be ‘ionizing’ but later any EM radiation such as the antenna of a hand held two way radio would do with low energy CMOS chips.

This was due to metastability. In practice the logic gates we use are very high gain analog amplifiers that are designed to “crash into the rails”. Some logic such as ECL was actually kept linear to get speed advantages but these days it’s all a bit murky.

The point is as the level at a simple logic gate input changes it goes through a transition region where the relationship between the gate input and output is indeterminate. Thus an inverter in effect might or might not invert or even oscillate with the input in the transition zone.

I won’t go into the reasons behind it but it’s down to two basic issues. Firstly the universe is full of noise, secondly it’s full of quantum effects. The two can be difficult to differentiate in even very long term measurements and engineers tend to try to lump it all under a first approximation of a Gaussian distribution as “Addative White Gaussian Noise”(AWGN) that has nice properties such as averaging predictably to zero with time and “the root of the mean squared”. However the universe tends not to play that way when you get up close, so instead “Phase Noise in a measurement window” is often used with Allan Deviation. //

There are things we can not know because they are unpredictable or beyond or ability to measure.

But also beyond a deterministic system to calculate.

Computers only know “natural numbers” or “unsigned integers” within a finite range. Everything else is approximated or as others would say “faked”. Between every natural number there are other numbers some can be found as ratios of natural numbers and others can not. What drove philosophers and mathematicians mad was the realisation of the likes of “root two”, pi and that there was an infinity of such numbers we could never know. Another issue was the spaces caused by integer multiplication the smaller all the integers the smaller the spaces between the multiples. Eventually it was realised that there was an advantage to this in that it scaled. The result in computers is floating point numbers. They work well for many things but not with addition and subtraction of small values with large values.

As has been mentioned LLM’s are in reality no different from “Digital Signal Processing”(DSP) systems in their fundamental algorithms. One of which is “Multiply and ADd”(MAD) using integers. These have issues in that values disappear or can not be calculated. With continuous signals they can be integrated in with little distortion. In LLM’s they can cause errors that are part of what has been called “Hallucinations”. That is where something with meaning to a human such as the name of a Pokemon trading card character “Solidgoldmagikarp” gets mapped to an entirely unrelated word “distribute”, thus mayhem resulted on GPT-3.5 and much hilarity once widely known.