Re: The amount of times...

Hmmm, 100C is where the vapor pressure of pure water is the standard atmospheric pressure at sea level. At 1 to 1.5km of elevation, the drop in temperature at where the vapor pressure of water is equal to the ambient pressure is enough to require adjustments to recipes when baking. The more natural point for 0C would be the triple point in water. Fahrenheit's scale was 0F being the coldest achievable temperature with water ice and NaCl, with 100F being core body temperature. A real SI scale fr temperature would be eV...

For doing thermodynamic calculations, the appropriate scales are Kelvin and Rankine, and there really isn't much difference in usability between K and R as all sorts of conversions need to be done to get answers in Joules or MWHr. Another "fun" problem is dealing with speed involves Joules being watt-seconds, while vehicle speeds are usually given in statute miles, nautical miles or kilometers per hour. A fun factoid is that 1 pound of force at one statute mile per hour is equal to 2.0W (1.99W is a closer approximation).

As for feet, a fair approximation is that light travels 1 ft/nsec, too bad the foot wasn't ~1.6% shorter as a light nano-second would be the ultimate SI unit of length. The current definition of an inch, 25.4mm, was chosen in the 1920's to allow machine tools to handle inches by having a 127 tooth gear instead of a 100 tooth gear.

FWIW, Jefferson wanted to base his unit of length on a "second's" rod, i.e. e pendulum whose length would have exactly one second period when measured at seal level and 45º latitude.

Don't get me started on kilograms of thrust.

Friday 27th January 2023 06:22 GMT

IvyKing

Reply Icon

Re: The amount of times...

From somewhere in the later half of the 19th century to ~1920, the US inch was defined as 39.37 inches equals 1m. According a ca 1920 issue of Railway Mechanical Engineer, the machine tool industry was making a push to defining the inch 25.4mm so that by using a 127 tooth gear to replace a 100 tooth gear a lathe could be set up to produce metric and imperial threads.

One problem with converting the US to pure metric is that almost all land titles use feet, not meters. The US legal definition of a foot was 1/66 of a chain, a mile was 80 chains (66x80=5280), a section of land under the Northwest Ordnance of 1787 (passed under the Articles of Confederation, NOT the Constitution), which was 6400 square chains and the acre being 10 square chains (640 acres per square mile). The surveys for the Townships (36 sections) didn't really start until ca 1796, so if the arrival of the metric standards had not been delayed by the storm and the English, the US might have re-written the 1787 law to use metric measurements.

Another problem with the US converting to metric was Herbert Hoover's success as Secretary of Commerce in setting national standards for pipes and other hardware.

One final note about metric versus imperial is that a nautical mile is defined as 1 minute of longitude at the equator, so works well with the degrees, minutes and seconds customarily used for angles. Metric navigation would favor a decimal system for expressing angles, i.e. the gradians.

doublelayerSilver badge

Reply Icon

Re: The amount of times...

"Fahrenheit's scale was 0F being the coldest achievable temperature with water ice and NaCl, with 100F being core body temperature."

Wrong on both counts. On Fahrenheit's original scale, 0 was the freezing point of a solution of ammonium chloride (NH4Cl), not table salt (NaCl). As neither compound is used directly on roads, the point at which it is not useful depends on which specific salt is being used in the area, and more importantly on where the compound has been applied and whether it has been moved or not. The temperature of the human body was not 100. It was 96. Of course, neither value is considered average for body temperature (and body temperature is incredibly variable in any case, whereas boiling points of things at a specific fixed pressure is stable). This is because the modern scale abandoned both limits by instead fixing 32 and 212 as the values for water freezing and boiling, moving both of the original bounds slightly and making use of the original scale inaccurate to modern users.

Wednesday 25th January 2023 01:55 GMT

-tim

Reply Icon

Coat

Re: The amount of times...

In 1700 it was much easier for a scientist to calibrate a home made thermometer using ammonium chloride cooling bath and a docile dog. The temperature of boiling water required a barometer at higher altitudes and calibration tables. The human armpit temperature of about 96 allows hand drawn hash marks in repeated halves. Many very early Fahrenheit thermometer are often marked every 3 degrees.

Monday 23rd January 2023 15:59 GMT

Michael Wojcik

Reply Icon

Re: The amount of times...

More importantly, for Fahrenheit the reference temperatures aren't 0 and 212; they're 32 and 96. 96 minus 32 is 64. And 32 and 64 are ... stay with me here ... powers of 2.

Fahrenheit based his scale on powers of 2 so that thermometers could be graduated by successive bisection (and then reflected to extrapolate outside that range, on the assumption that the mechanism was sufficiently linear within the desired range). That's an actual engineering reason, unlike "duh humans like powers of 10". There really isn't much reason to favor Celsius.

Kelvin, of course, is the one that matters. (Yes, Rankine works too, but for some SI operations Kelvin is more convenient.)

Celsius is today as much flavor-of-the-month as Fahrenheit is. The original justifications for them are no longer relevant; they're just a matter of taste.

Any gas can be converted into a liquid by simple compression, unless its temperature is below critical. Therefore, the division of substances into liquids and gases is largely conditional. The substances that we are used to considering as gases simply have very low critical temperatures and therefore cannot be in a liquid state at temperatures close to room temperature. On the contrary, the substances we classify as liquids have high critical temperatures (see table in §

).

All gases that make up the air (except carbon dioxide) have low critical temperatures. Their liquefaction therefore requires deep cooling.

There are many types of machines for producing liquid gases, in particular liquid air.

In modern industrial plants, significant cooling and liquefaction of gases is achieved by expansion under thermal insulation conditions.

Yakisugi is a Japanese architectural technique for charring the surface of wood. It has become quite popular in bioarchitecture because the carbonized layer protects the wood from water, fire, insects, and fungi, thereby prolonging the lifespan of the wood. Yakisugi techniques were first codified in written form in the 17th and 18th centuries. But it seems Italian Renaissance polymath Leonardo da Vinci wrote about the protective benefits of charring wood surfaces more than 100 years earlier, according to a paper published in Zenodo, an open repository for EU funded research. //

Leonardo produced more than 13,000 pages in his notebooks (later gathered into codices), less than a third of which have survived. //

In 2003, Alessandro Vezzosi, director of Italy’s Museo Ideale, came across some recipes for mysterious mixtures while flipping through Leonardo’s notes. Vezzosi experimented with the recipes, resulting in a mixture that would harden into a material eerily akin to Bakelite, a synthetic plastic widely used in the early 1900s. So Leonardo may well have invented the first manmade plastic. //

The benefits of this method of wood preservation have since been well documented by science, although the effectiveness is dependent on a variety of factors, including wood species and environmental conditions. The fire’s heat seals the pores of the wood so it absorbs less water—a natural means of waterproofing. The charred surface serves as natural insulation for fire resistance. And stripping the bark removes nutrients that attract insects and fungi, a natural form of biological protection.

The dress was a 2015 online viral phenomenon centred on a photograph of a dress. Viewers disagreed on whether the dress was blue and black, or white and gold. The phenomenon revealed differences in human colour perception and became the subject of scientific investigations into neuroscience and vision science.

The phenomenon originated in a photograph of a dress posted on the social networking platform Facebook. The dress was black and blue, but the conditions of the photograph caused many to perceive it as white and gold, creating debate. Within a week, more than ten million tweets had mentioned the dress. The retailer of the dress, Roman Originals, reported a surge in sales and produced a one-off version in white and gold sold for charity.

This comic shows two drawings of a woman wearing the same dress, but with different background (and body) colors. The two drawings are split with a narrow vertical portion of an image from the web.

The comic strip refers to a dress whose image went viral on Tumblr only hours before the strip was posted and soon showed up also on Reddit, Twitter, Wired and on The New York Times.

Due to the dress's particular color scheme and the exposure of the photo, it forms an optical illusion causing viewers to disagree on what color the dress actually seems to be. The xkcd strip sandwiches a cropped segment of the photographed dress between two drawings which use the colors from the image against different backgrounds, leading the eye to interpret the white balance differently, demonstrating how the dress can appear different colors depending on context and the viewer's previous experiences.

Both dresses have exactly the same colors actually: //

To the uninitiated, the color of the dress seems immediately obvious; when others cannot see it their way, it can be a surreal (even uncomfortable) experience.

As an aside, the retailer Roman Originals would later confirm the dress was blue with black lace, and that a white dress with gold lace was not offered among the clothing line.

We've learned a lot from the viral image.

The viral image holds a lesson in why people disagree—and how we can learn to better understand each other.

It was not a tranquil time. People argued with their friends about the very basics of reality. Spouses vehemently disagreed. Each and every person was on one side or the other side. It could be hard to imagine how anyone in their right mind could hold an opinion different from your own.

I’m talking, of course, about “the dress,” which went viral on Feb. 26, 2015. To recap: A cellphone picture of a wedding guest’s dress, uploaded to the internet, sharply divided people into those who saw it as white and gold and those who saw it in black and blue—even if they were viewing it together, on the very same computer or phone screen.

The notorious dress, under natural lighting conditions, is unambiguously black and blue, for (almost) everyone who saw it in person, or in other photographs. It was just the one image, snapped by a mother of a bride and uploaded to Tumblr by one of her daughter’s friends, that caused so much disagreement. How can it be that there is such strong consensus about the colors of the actual dress, but such striking disagreements about its colors in this particular image? This is not a debate about people seeing different shades of gray: blue and gold are categorically different colors, not even in the same neighborhood on the color wheel.

Does swearing make you stronger? Science says yes.

“A calorie-neutral, drug-free, low-cost, readily available tool for when we need a boost in performance.”

If you’re human, you’ve probably hollered a curse word or two (or three) when barking your shin on a table edge or hitting your thumb with a hammer. Perhaps you’ve noticed that this seems to lessen your pain. There’s a growing body of scientific evidence that this is indeed the case. The technical term is the “hypoalgesic effect of swearing.” Cursing can also improve physical strength and endurance, according to a new paper published in the journal American Psychologist.

As previously reported, co-author Richard Stephens, a psychologist at Keele, became interested in studying the potential benefits of profanity after noting his wife’s “unsavory language” while giving birth and wondered if profanity really could help alleviate pain. “Swearing is such a common response to pain. There has to be an underlying reason why we do it,” Stephens told Scientific American after publishing a 2009 study that was awarded the 2010 Ig Nobel Peace Prize. //

The team followed up with a 2011 study showing that the pain-relief effect works best for subjects who typically don’t swear that often, perhaps because they attach a higher emotional value to swears. They also found that subjects’ heart rates increased when they swore. But it might not be the only underlying mechanism. Other researchers have pointed out that profanity might be distracting, thereby taking one’s mind off the pain rather than serving as an actual analgesic. //

UserIDAlreadyInUse Ars Tribunus Angusticlavius

12y

6,810

Subscriptor

<psst> "Hey, buddy."

"Yeah?"

"You got a game coming up, yeah?"

"Yeah."

"Need a boost? I got some curse words guaranteed to boost your performance."

"Oh, uh...they check for that now. #!$@, $#!@, and even *&!%!! they test for."

"Yeah, yeah, but I got &!$#!!! and !!^%@$, virtually undetectable. You memorize these, pass the cursing check, and I guarantee you'll have the #!$@ing edge when you need it!" //

etxdm Ars Centurion

5y

315

Subscriptor

They need to study overuse versus occasional use. I've always thought a well placed swear word is far more effective than rampant overuse. I was recently waiting for a drink at a bar and some bro was literally using f*** every other word. It was exhausting trying to filter his speech to understand what he was trying to say.

The emergence of synthetic pigments in the 19th century had an immense impact on the art world, particularly the availability of emerald-green pigments, prized for their intense brilliance by such masters as Paul Cézanne, Edvard Munch, Vincent van Gogh, and Claude Monet. The downside was that these pigments often degraded over time, resulting in cracks and uneven surfaces and the formation of dark copper oxides—even the release of arsenic compounds.

Naturally, it’s a major concern for conservationists of such masterpieces. So it should be welcome news that European researchers have used synchrotron radiation and various other analytical tools to determine whether light and/or humidity are the culprits behind that degradation and how, specifically, it occurs, according to a paper published in the journal Science Advances. //

The results: In the mockups, light and humidity trigger different degradation pathways in emerald-green paints. Humidity results in the formation of arsenolite, making the paint brittle and prone to flaking. Light dulls the color by causing trivalent arsenic already in the pigment to oxidize into pentavalent compounds, forming a thin white layer on the surface. Those findings are consistent with the analyzed samples taken from The Intrigue, confirming the degradation is due to photo-oxidation. Light, it turns out, is the greatest threat to that particular painting, and possibly other masterpieces from the same period.

Playing the Game

Goal: Win by scoring the most points after 10 questions.

How to Play

Each player gets 1 whiteboard and 10 voting tokens of their color.

The player who most recently watched a Veritasium video starts as the Question Reader.

The role of Question Reader moves clockwise each round.

The game lasts 10 questions.

Each Round

The Question Reader reads a card out loud (without taking it out of the box). Starting with the player to their left, everyone places one voting token face down on the mat.

Each chip can only be played once; if placed on the correct answer it is retained, if not it is discarded.

Players choose which token to use based on confidence:

- High number = high confidence.

- Low number = low confidence

Scoring Each Question

The Question Reader reveals the correct answer.

If you were right, move your token to your scoring pile.

If you were wrong, your token is discarded.

Game End: After 10 questions, all tokens will have been used. Players add up the numbers on their scoring piles. The player with the highest total wins!

Popular science Youtuber Veritasium has their own board game coming out - Elements of Truth is a trivia game where it's not what you know, it's what you you know that counts.

It sounds a lot like the Jurassic Park "Underwear Gnomes" technique of generic engineering:

- Find and extract DNA

- Squeeze DNA into an ostrich egg

- ???

- Dinosaur!

In the past few years, many environmental and academic activists have been undermining the work of Norman Borlaug and the successes of the Green Revolution by publishing false information. The environmental activists behind these headlines claim that the Green Revolution failed. Here is a random sample of examples of these activists lying to the public. //

Fortunately, evidence easily refutes the misinformation spread by such activists’ claims. Wheat yields rose dramatically in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s. By lying to their audience and the public, these groups are ignoring that wheat yields in India more than doubled between the period of 1967 and 1972.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0111629

There’s no “new research” as claimed by the above activist headlines. The evidence is clear: the Green Revolution resulted in higher crop yields that contributed to preventing one billion deaths from starvation. Dr. Borlaug made an amazing contribution to improving global food security. In 1970, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work.

I can’t believe I caught THIS on camera… a bee having a wee! 🐝👇

Yep, it turns out that bees do wee, well kind of – but not like we do. Apparently they’ve got a clever little system that gets rid of wee and poop in one go, usually mid-flight, so they don’t mess up the hive (that’s very well trained!)

It’s normally such a blink-and-you-miss-it thing… but while I was filming the echinops in full bloom at @fieldgateflowers this week, one bee just went for it right in front of me.

Most people would recognize the device in the image above, although they probably wouldn't know it by its formal name: the Crookes radiometer. As its name implies, placing the radiometer in light produces a measurable change: the blades start spinning. //

It's quite common—and quite wrong—to see explanations of the Crookes radiometer that involve radiation pressure. Supposedly, the dark sides of the blades absorb more photons, each of which carries a tiny bit of momentum, giving the dark side of the blades a consistent push. The problem with this explanation is that photons are bouncing off the silvery side, which imparts even more momentum. If the device were spinning due to radiation pressure, it would be turning in the opposite direction than it actually does.

An excess of the absorbed photons on the dark side is key to understanding how it works, though. Photophoresis operates through the temperature difference that develops between the warm, light-absorbing dark side of the blade and the cooler silvered side. //

But a Crookes radiometer is in a sealed glass container with a far lower air pressure. This allows the gas molecules to speed off much farther from the dark surface of the blade before they run into anything, creating an area of somewhat lower pressure at its surface. That causes gas near the surface of the shiny side to rush around and fill this lower-pressure area, imparting the force that starts the blades turning.

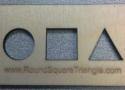

Seemingly unsolvable, solved.

Can you imagine a single solid object that is simultaneously a Circle, a Square, and a Triangle without altering its form in any way?

It turns out, pushing unrealistic green energy schemes onto low- and middle-income people at the expense of a safer fuel source was not only bad science, it was dangerous propaganda.

The feathers can emit two frequencies of laser light from multiple regions across their colored eyespots. //

Peacock feathers are greatly admired for their bright iridescent colors, but it turns out they can also emit laser light when dyed multiple times, according to a paper published in the journal Scientific Reports. Per the authors, it's the first example of a biolaser cavity within the animal kingdom.

As previously reported, the bright iridescent colors in things like peacock feathers and butterfly wings don't come from any pigment molecules but from how they are structured. The scales of chitin (a polysaccharide common to insects) in butterfly wings, for example, are arranged like roof tiles. Essentially, they form a diffraction grating, except photonic crystals only produce certain colors, or wavelengths, of light, while a diffraction grating will produce the entire spectrum, much like a prism.

Both are naturally occurring examples of what physicists call photonic crystals. Also known as photonic bandgap materials, photonic crystals are "tunable," which means they are precisely ordered in such a way as to block certain wavelengths of light while letting others through. Alter the structure by changing the size of the tiles, and the crystals become sensitive to a different wavelength. (In fact, the rainbow weevil can control both the size of its scales and how much chitin is used to fine-tune those colors as needed.).

Even better (from an applications standpoint), the perception of color doesn't depend on the viewing angle. //

quackmeister Wise, Aged Ars Veteran

8y

162

If this didn't already appear in a scene from the Incredibles set in the villain's palatial gardens, it should have. //

Chuckstar Ars Legatus Legionis

22y

35,919

Gives me an opportunity to link to my favorite video of a wild peacock in action. In case anyone wondered if the peacock's tail really acted as a proxy that the individual had to be fit enough to simply survive carrying such a thing around (if the embedded time stamp doesn't work, the action starts at 1:15):

Removable transparent films apply digital restorations directly to damaged artwork.

MIT graduate student Alex Kachkine once spent nine months meticulously restoring a damaged baroque Italian painting, which left him plenty of time to wonder if technology could speed things up. Last week, MIT News announced his solution: a technique that uses AI-generated polymer films to physically restore damaged paintings in hours rather than months. The research appears in Nature.

Kachkine's method works by printing a transparent "mask" containing thousands of precisely color-matched regions that conservators can apply directly to an original artwork. Unlike traditional restoration, which permanently alters the painting, these masks can reportedly be removed whenever needed. So it's a reversible process that does not permanently change a painting.

"Because there's a digital record of what mask was used, in 100 years, the next time someone is working with this, they'll have an extremely clear understanding of what was done to the painting," Kachkine told MIT News. "And that's never really been possible in conservation before."

Nature reports that up to 70 percent of institutional art collections remain hidden from public view due to damage—a large amount of cultural heritage sitting unseen in storage. Traditional restoration methods, where conservators painstakingly fill damaged areas one at a time while mixing exact color matches for each region, can take weeks to decades for a single painting. It's skilled work that requires both artistic talent and deep technical knowledge, but there simply aren't enough conservators to tackle the backlog. //

For now, the method works best with paintings that include numerous small areas of damage rather than large missing sections. In a world where AI models increasingly seem to blur the line between human- and machine-created media, it's refreshing to see a clear application of computer vision tools used as an augmentation of human skill and not as a wholesale replacement for the judgment of skilled conservators.

Today marks the 50th anniversary of Jaws, Steven Spielberg's blockbuster horror movie based on the bestselling novel by Peter Benchley. We're marking the occasion with a tribute to this classic film and its enduring impact on the popular perception of sharks, shark conservation efforts, and our culture at large. //

A lot of folks in both the marine science world and the ocean conservation communities have reported that Jaws in a lot of ways changed our world. It's not that people used to think that sharks were cute, cuddly, adorable animals, and then after Jaws, they thought that they were bloodthirsty killing machines. They just weren't on people's minds. Fishermen knew about them, surfers thought about them, but that was about it. Most people who went to the beach didn't pay much mind to what could be there. Jaws absolutely shattered that. My parents both reported that the summer that Jaws came out, they were afraid to go swimming in their community swimming pools. //

The movie also was the first time that a scientist was the hero. People half a generation above me have reported that seeing Richard Dreyfuss' Hooper on the big screen as the one who saves the day changed their career trajectory. "You can be a scientist who studies fish. Cool. I want to do that." In the time since Jaws came out, a lot of major changes have happened. One is that shark populations have declined globally by about 50 percent, and many species are now critically endangered. //

And then, from a cultural standpoint, we now have a whole genre of bad shark movies.

Ars Technica: Sharknado!

David Shiffman: Yes! Sharknado is one of the better of the bunch. Sitting on my desk here, we've got Sharkenstein, Raiders of the Lost Shark, and, of course, Shark Exorcist, all from the 2010s. I've been quoted as saying there's two types of shark movie: There's Jaws and there's bad shark movies. //

Ars Technica: People have a tendency to think that sharks are simply brutal killing machines. Why are they so important to the ecosystem?

David Shiffman: The title of my book is Why Sharks Matter because sharks do matter and people don't think about them that way. These are food chains that provide billions of humans with food, including some of the poorest humans on Earth. They provide tens of millions of humans with jobs. When those food chains are disrupted, that's bad for coastal communities, bad for food security and livelihoods. If we want to have healthy ocean food chains, we need a healthy top of the food chain, because when you lose the top of the food chain, the whole thing can unravel in unpredictable, but often quite devastating ways.

So sharks play important ecological roles by holding the food chain that we all depend on in place. They're also not a significant threat to you and your family. More people in a typical year die from flower pots falling on their head when they walk down the street. More people in a typical year die falling off a cliff when they're trying to take a selfie of the scenery behind them, than are killed by sharks. Any human death or injury is a tragedy, and I don't want to minimize that. But when we're talking about global-scale policy responses, the relative risk versus reward needs to be considered. //

In all of recorded human history, there is proof that exactly one shark bit more than one human. That was the Sharm el-Sheikh attacks around Christmas in Egypt a few years ago. Generally speaking, a lot of times it's hard to predict why wild animals do or don't do anything. But if this was a behavior that was real, there would be evidence that it happens and there isn't any, despite a lot of people looking. //

One of my favorite professional experiences is the American Alasdair Rank Society conference. One year it was in Austin, Texas, near the original Alamo Drafthouse. Coincidentally, while we were there, the cinema held a "Jaws on the Water" event. They had a giant projector screen, and we were sitting in a lake in inner tubes while there were scuba divers in the water messing with us from below. I did that with 75 professional shark scientists. It was absolutely amazing. It helped knowing that it was a lake.

Ars Technica: If you wanted to make another really good shark movie, what would that look like today?

David Shiffman: I often say that there are now three main movie plots: a man goes on a quest, a stranger comes to town, or there's a shark somewhere you would not expect a shark to be. It depends if you want to make a movie that's actually good, or one of the more fun "bad" movies like Sharknado or Sharktopus or Avalanche Sharks—the tagline of which is "snow is just frozen water." These movies are just off the rails and absolutely incredible. The ones that don't take themselves too seriously and are in on the joke tend to be very fun.

you got it.

Exploring the Spectrum, a groundbreaking 1974 documentary by Dr. John Nash Ott.

A captivating journey into the science of photobiology and the profound impact of light on health.

A pioneer in time-lapse photography and full-spectrum lighting, Dr. Ott reveals how natural and artificial light influences the growth, behavior, and well-being of plants, animals, and humans.

Through mesmerizing visuals and innovative experiments, the film challenges conventional wisdom, questioning whether fluorescent lights, UV-blocking glasses, and indoor lifestyles contribute to health issues like cancer, learning disorders, and immune system weaknesses.

Ott’s work highlights the essential role of natural sunlight and balanced light frequencies in sustaining life, urging us to rethink our relationship with the light that surrounds us.